conservation of books

Books can be challenging to conserve because they have value in both form and function; they might still be actively used for the text or other information they contain, or they may be interesting or important due to their binding styles, or evidence of previous wear. Many times they have been rebound at least once since the initial binding, in periods when the covering was seen as a stylistic choice more than an artefact of cultural heritage. They might fail structurally because of intense use over centuries, or because of poor quality materials or construction that fails to last ten years.

There are often varying levels of intervention that are possible; in general, we try to preserve as much original structure and material as possible, in a “first do no harm” type of approach.

case study

st nicholas’ church (thames ditton)

1592 “Breeches Bible”

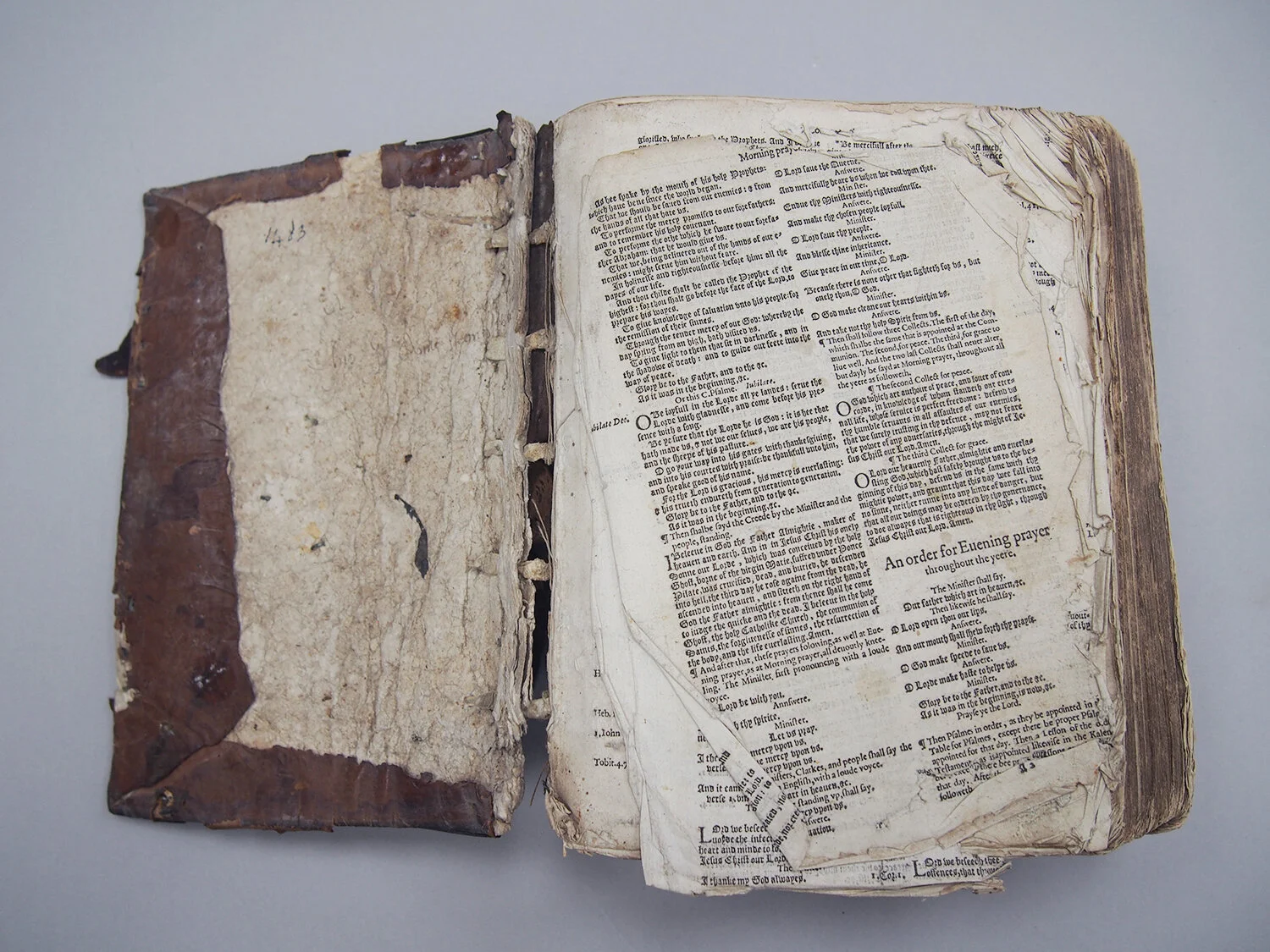

The Breeches Bible is an edition of the Geneva Bible nicknamed for its use of that word to describe the fig leaf clothing fashioned by Adam & Eve. This one belonged to a church that we were really thrilled to discover understood that it wasn’t worth a huge amount monetarily because of the numerous copies of this book and its poor mechanical condition, but they felt moved to do something to preserve their bit of cultural heritage.

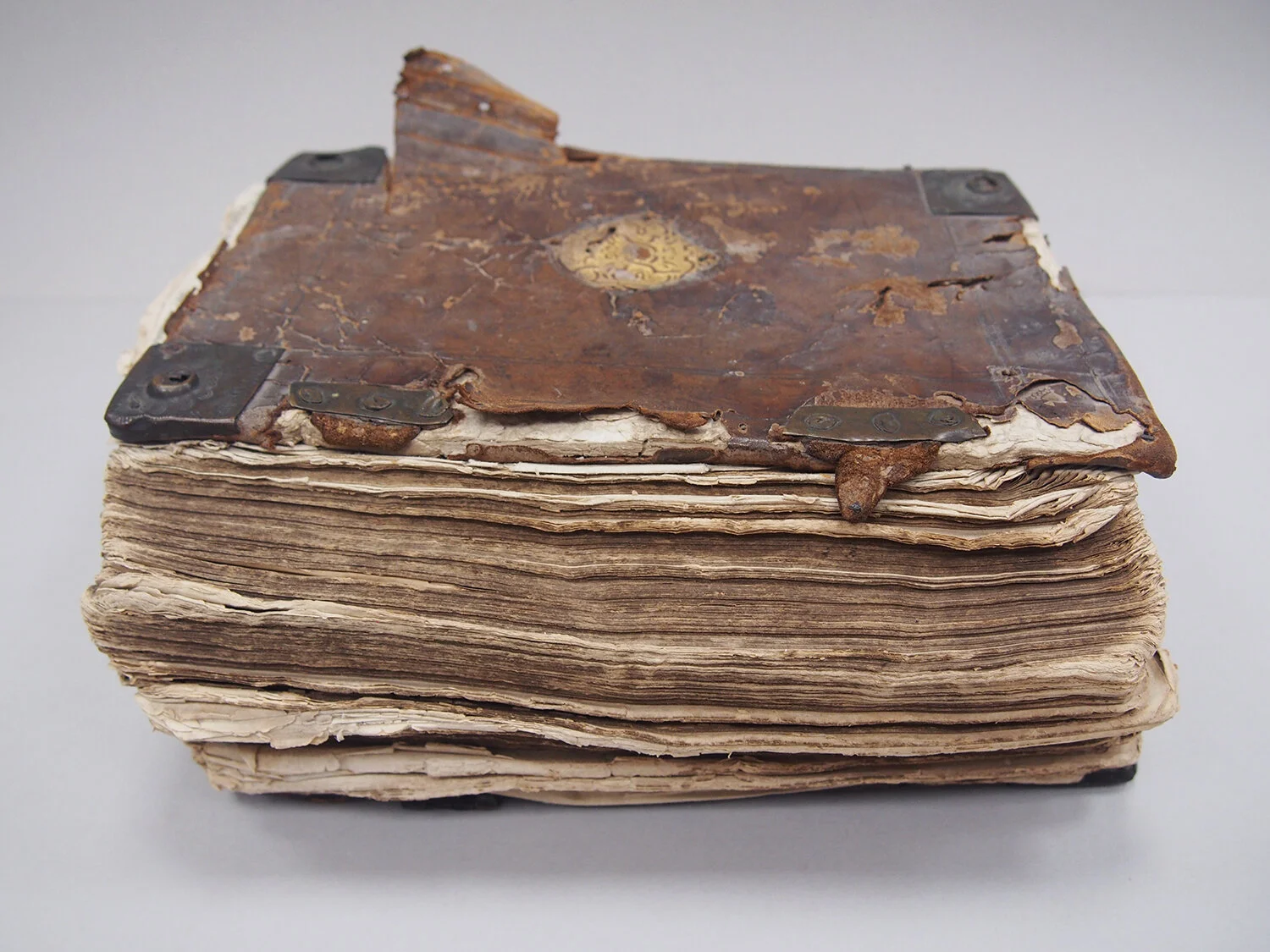

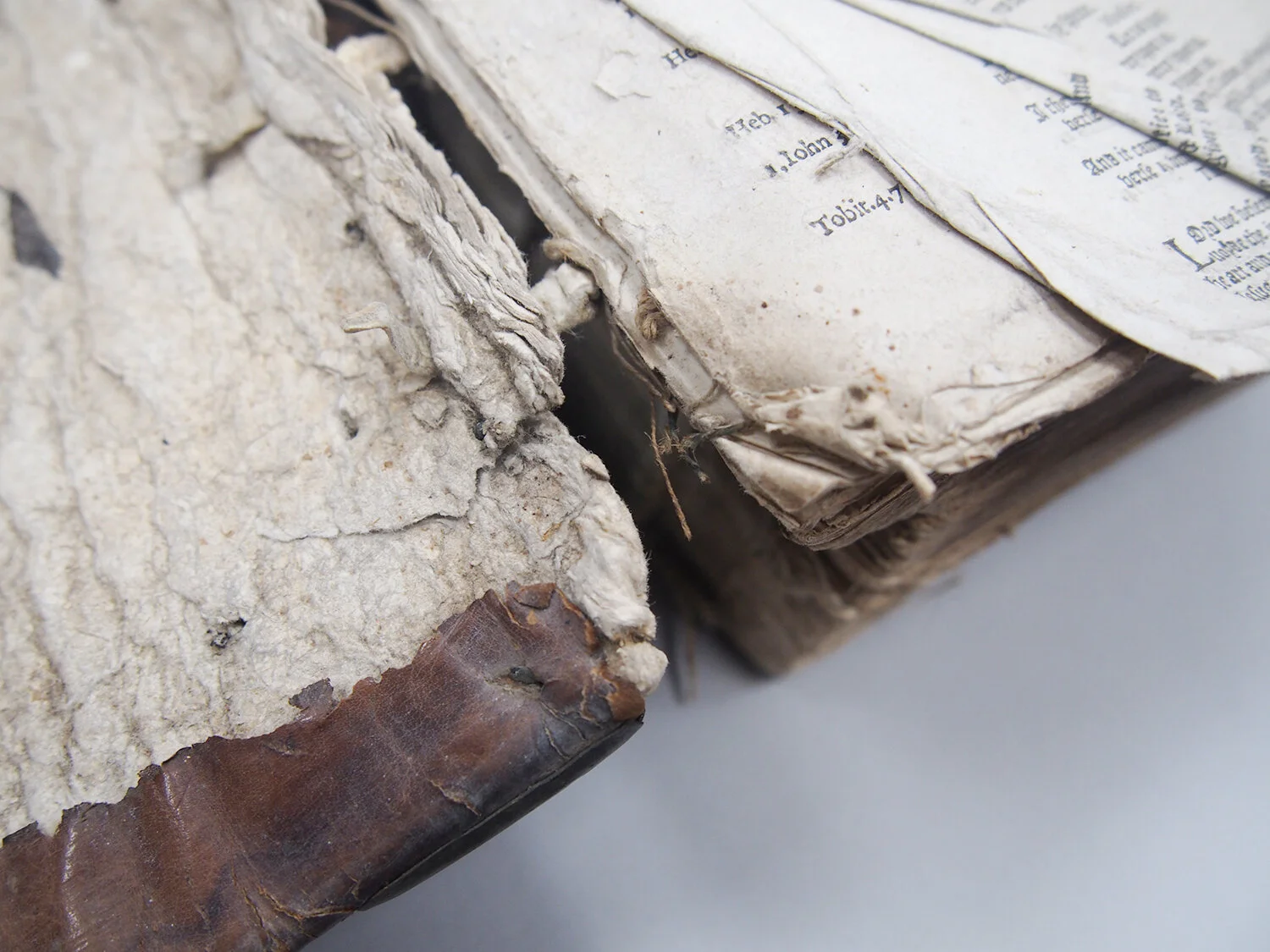

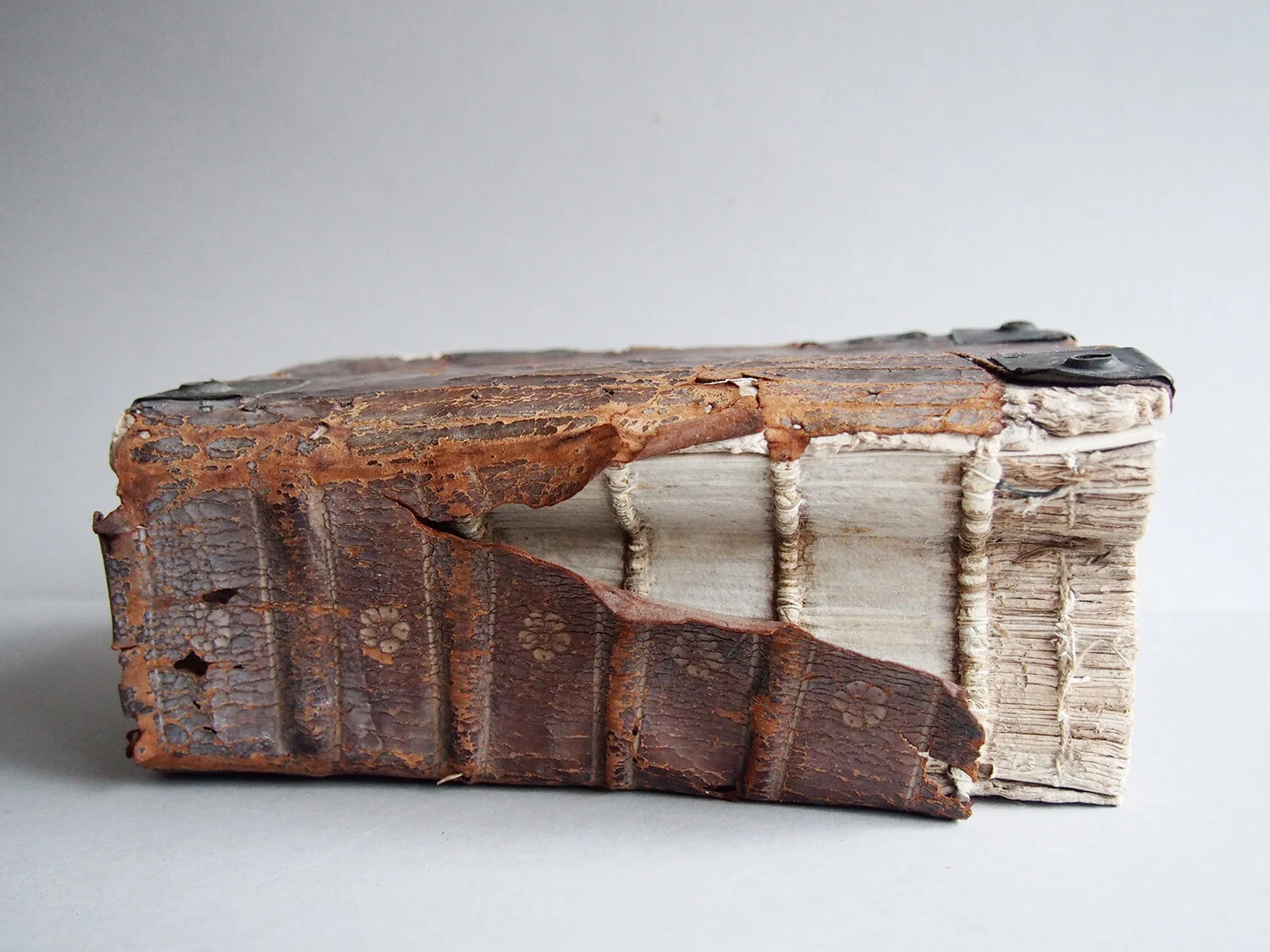

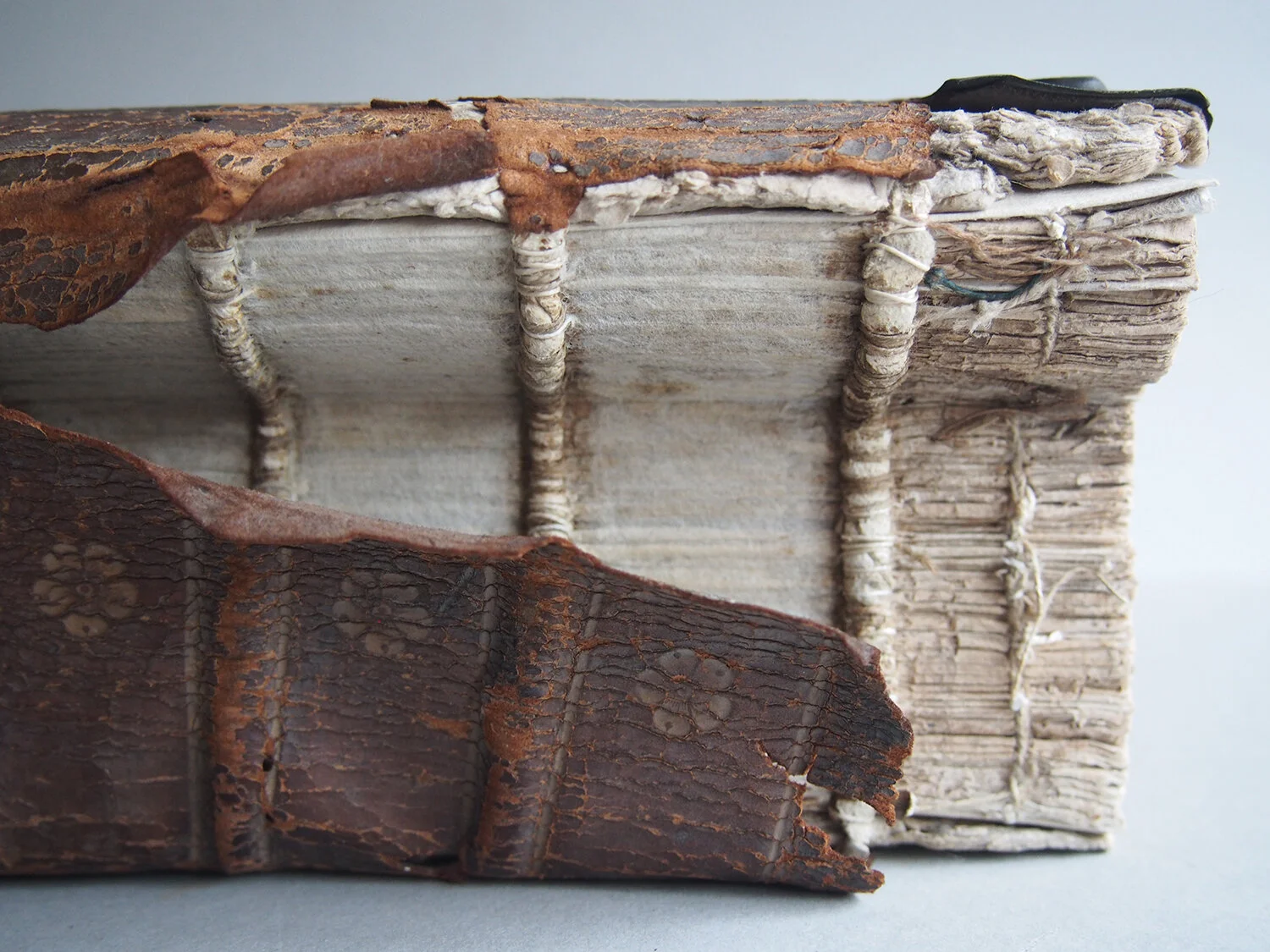

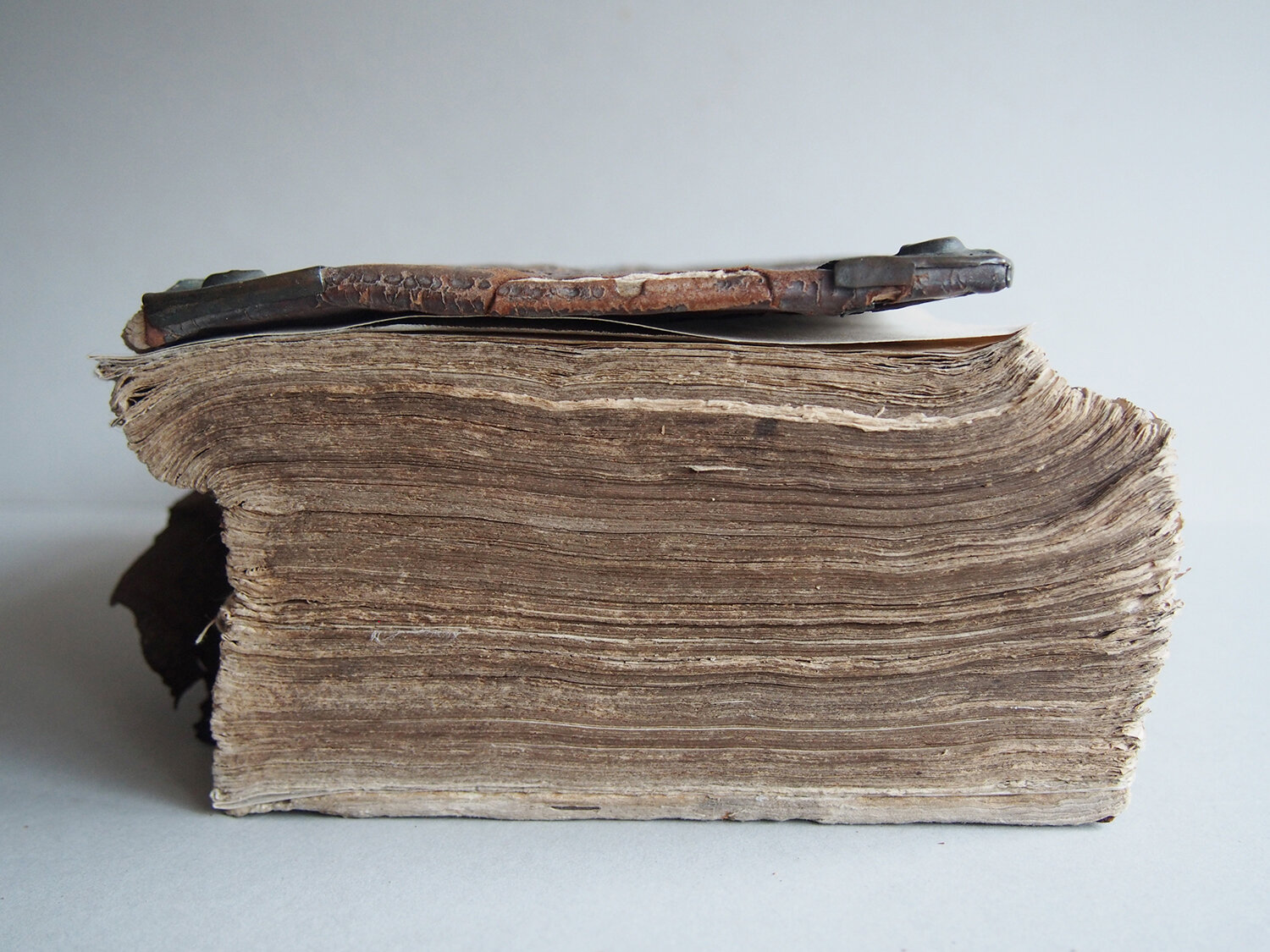

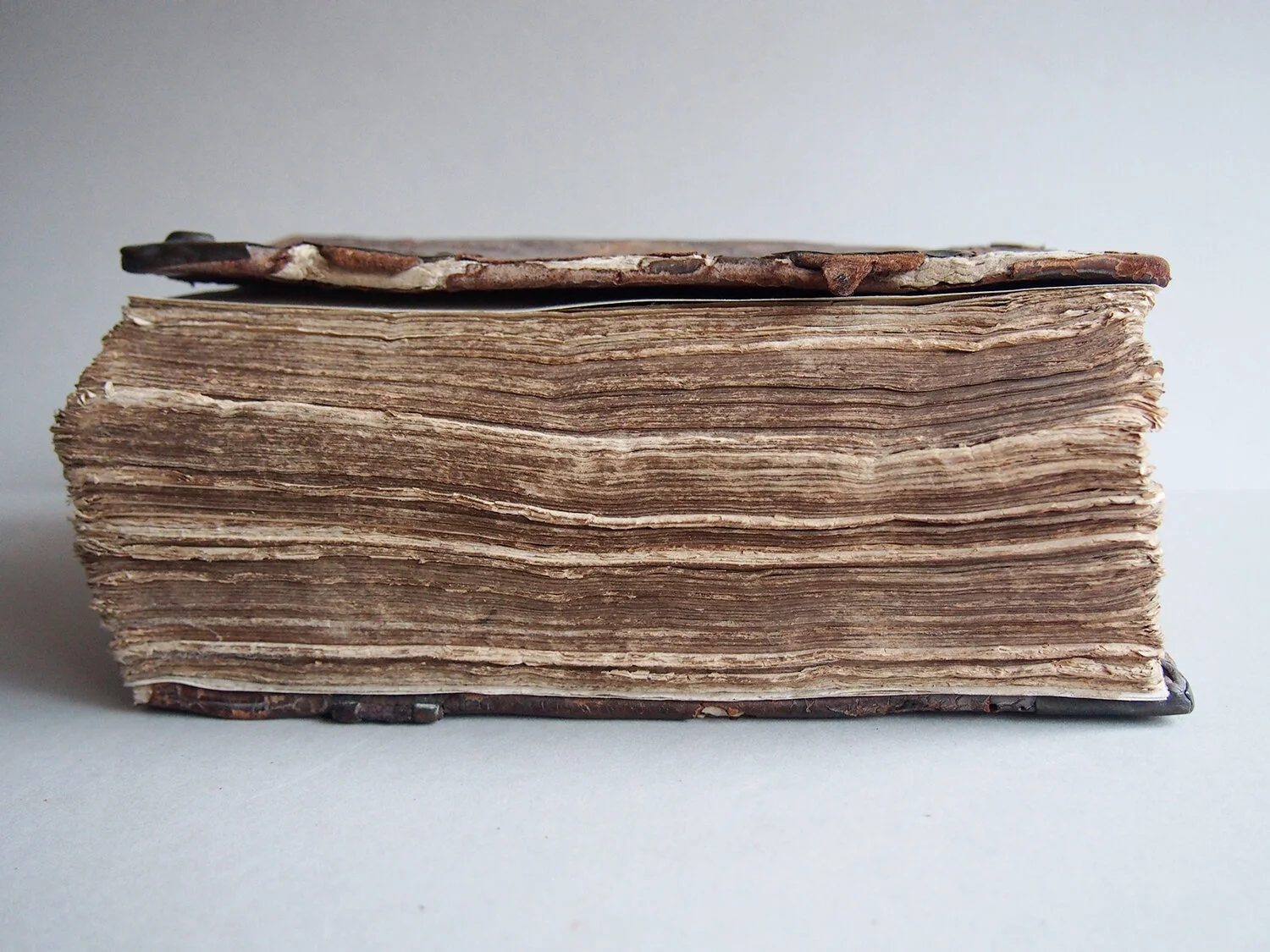

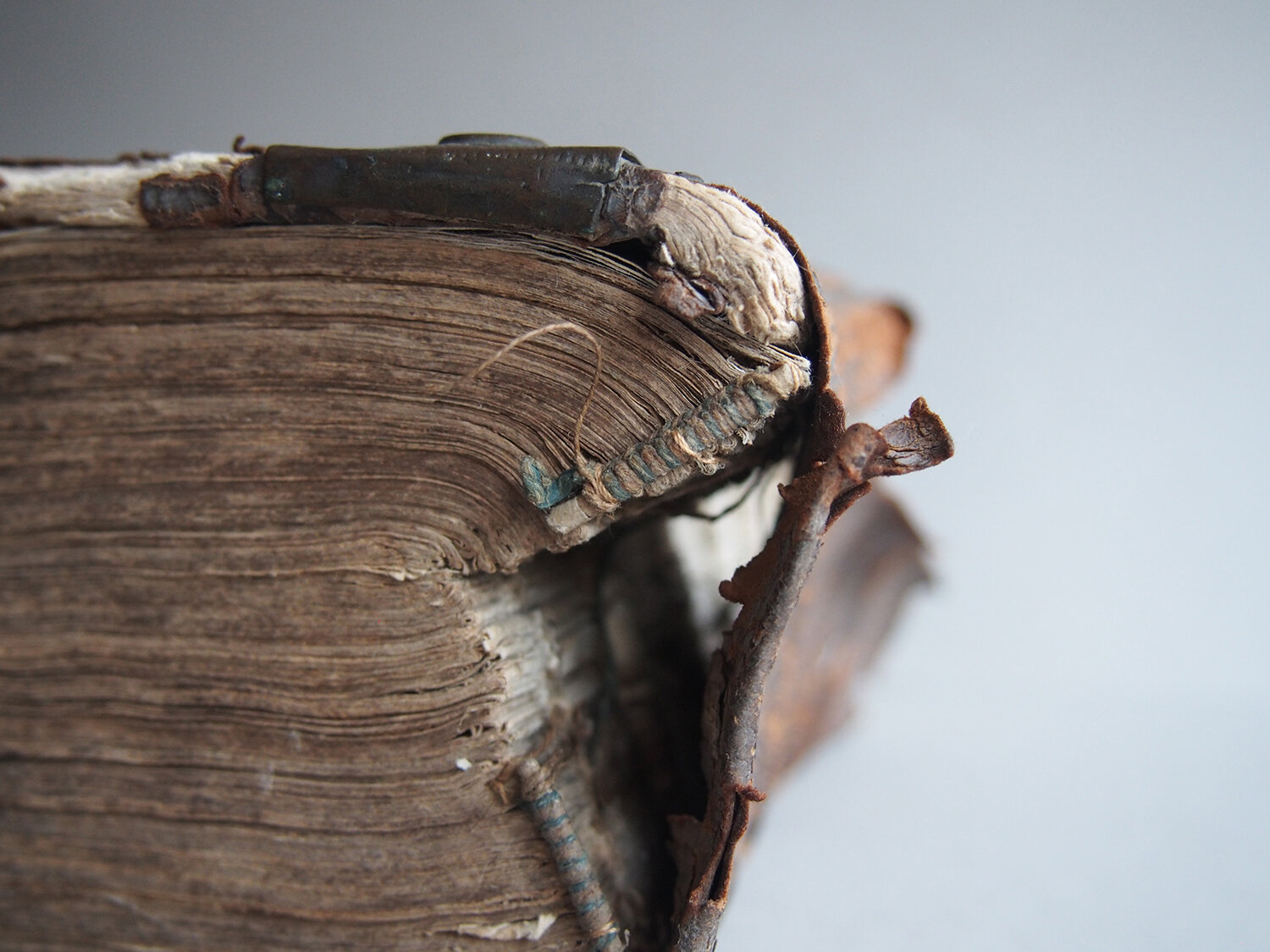

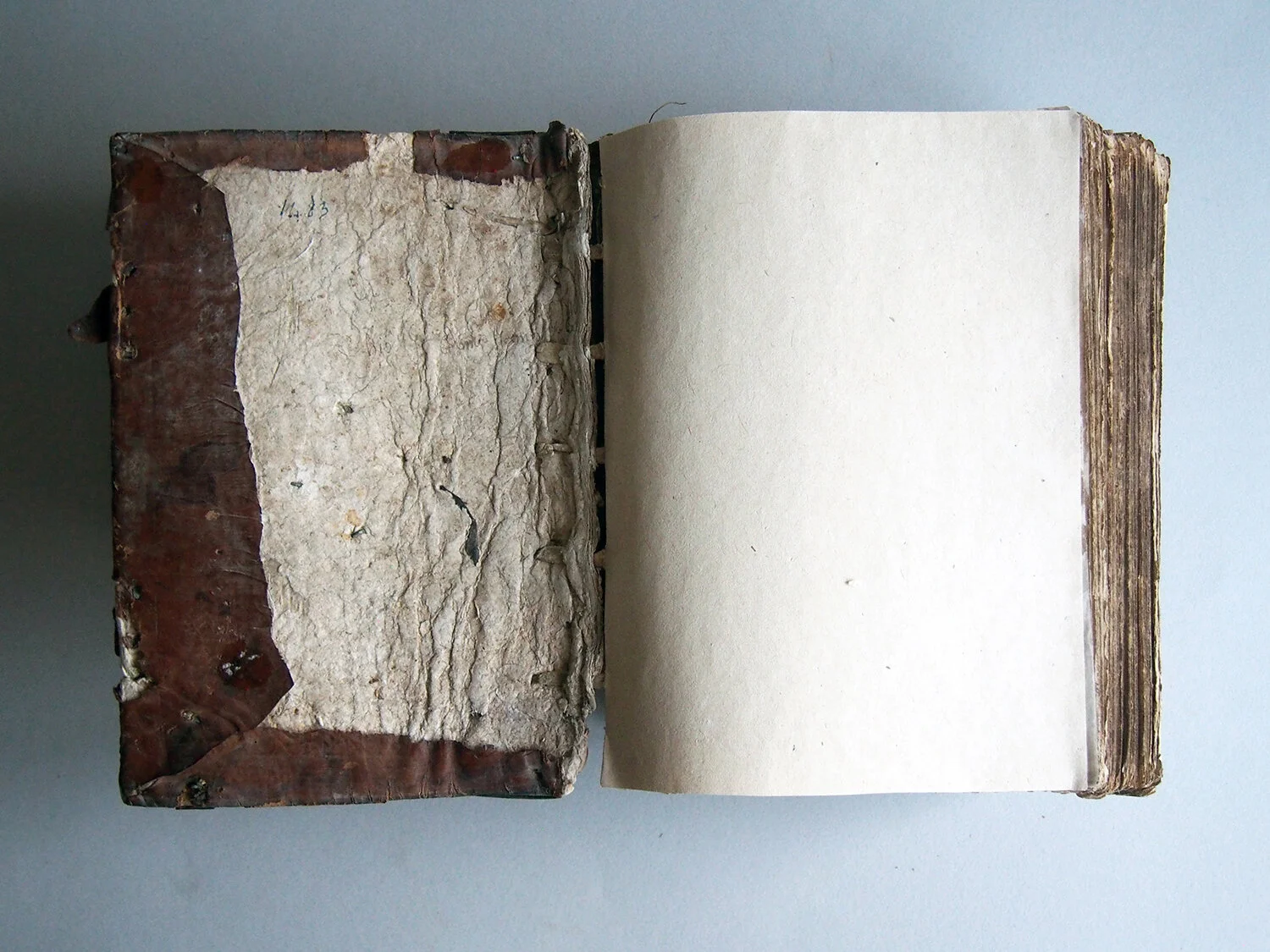

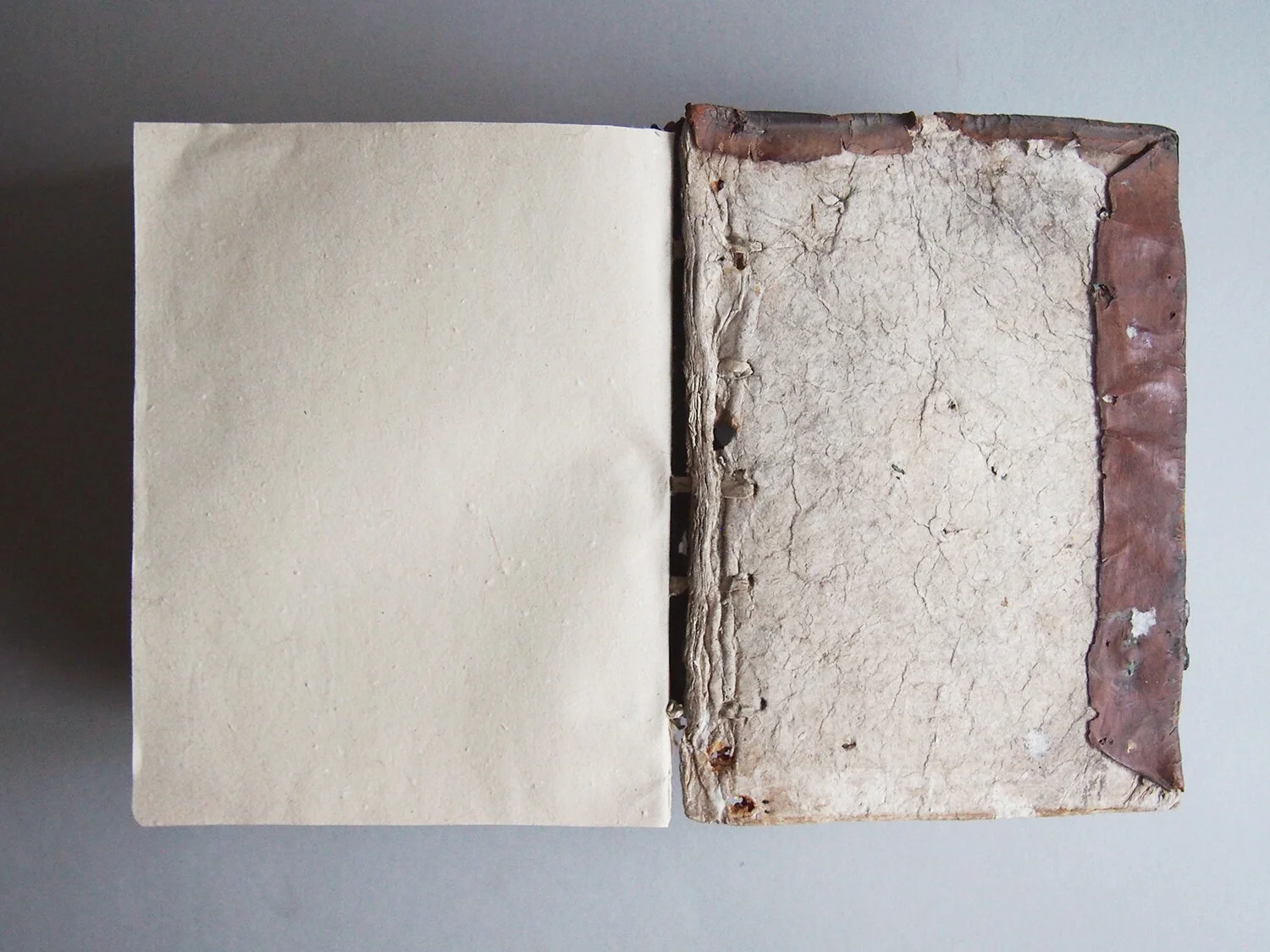

The binding is all original: the many sections were sewn onto raised alum tawed supports, with pulp boards and a relatively simple leather covering. A common problem with leather, especially when it is no longer adhered to the binding, is that it can shrink minimally over time, and here there seemed to be that shrinkage on the spine—either causing or facilitated by the distorted shape of the textblock which could no longer be straightened.

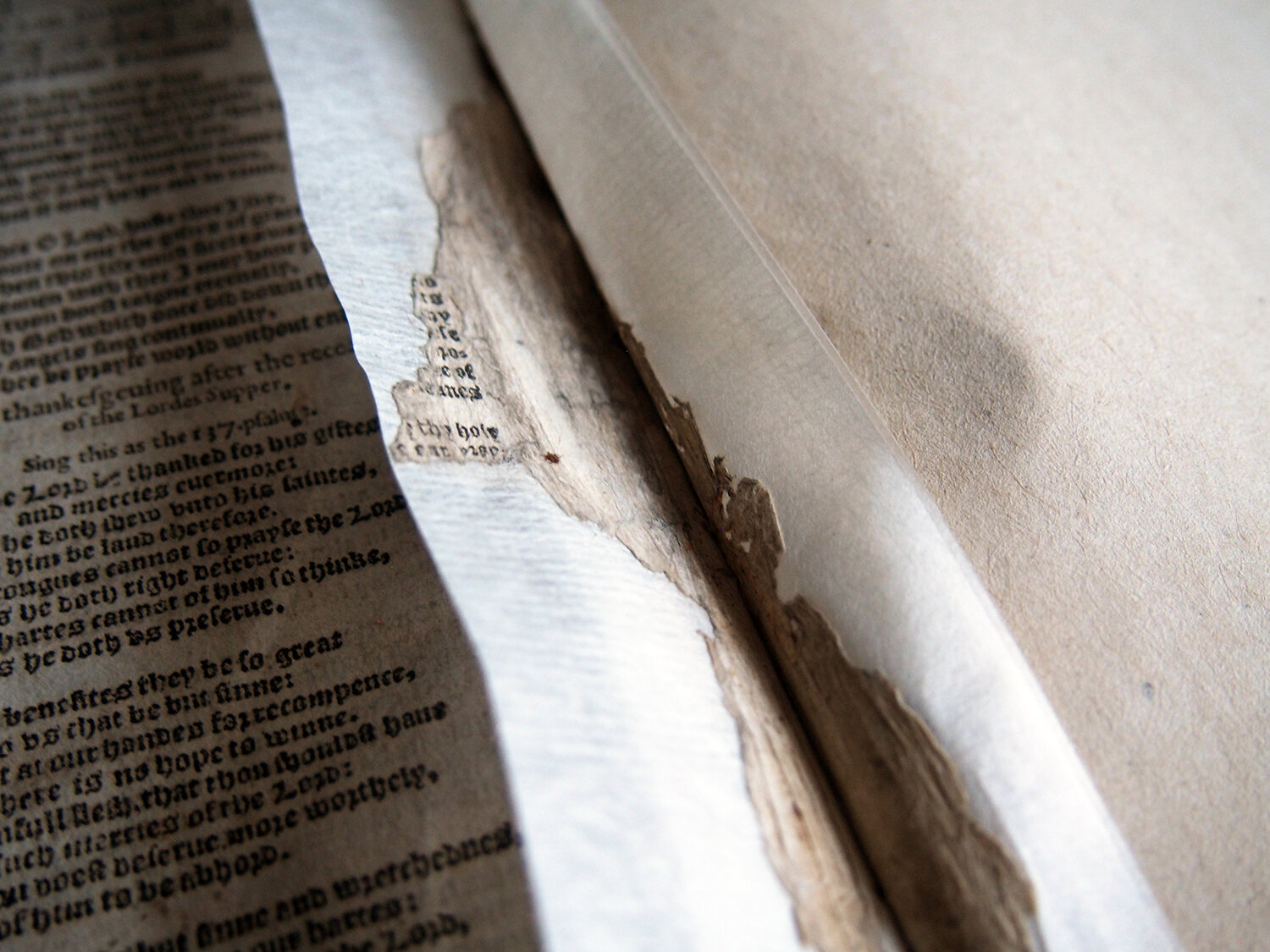

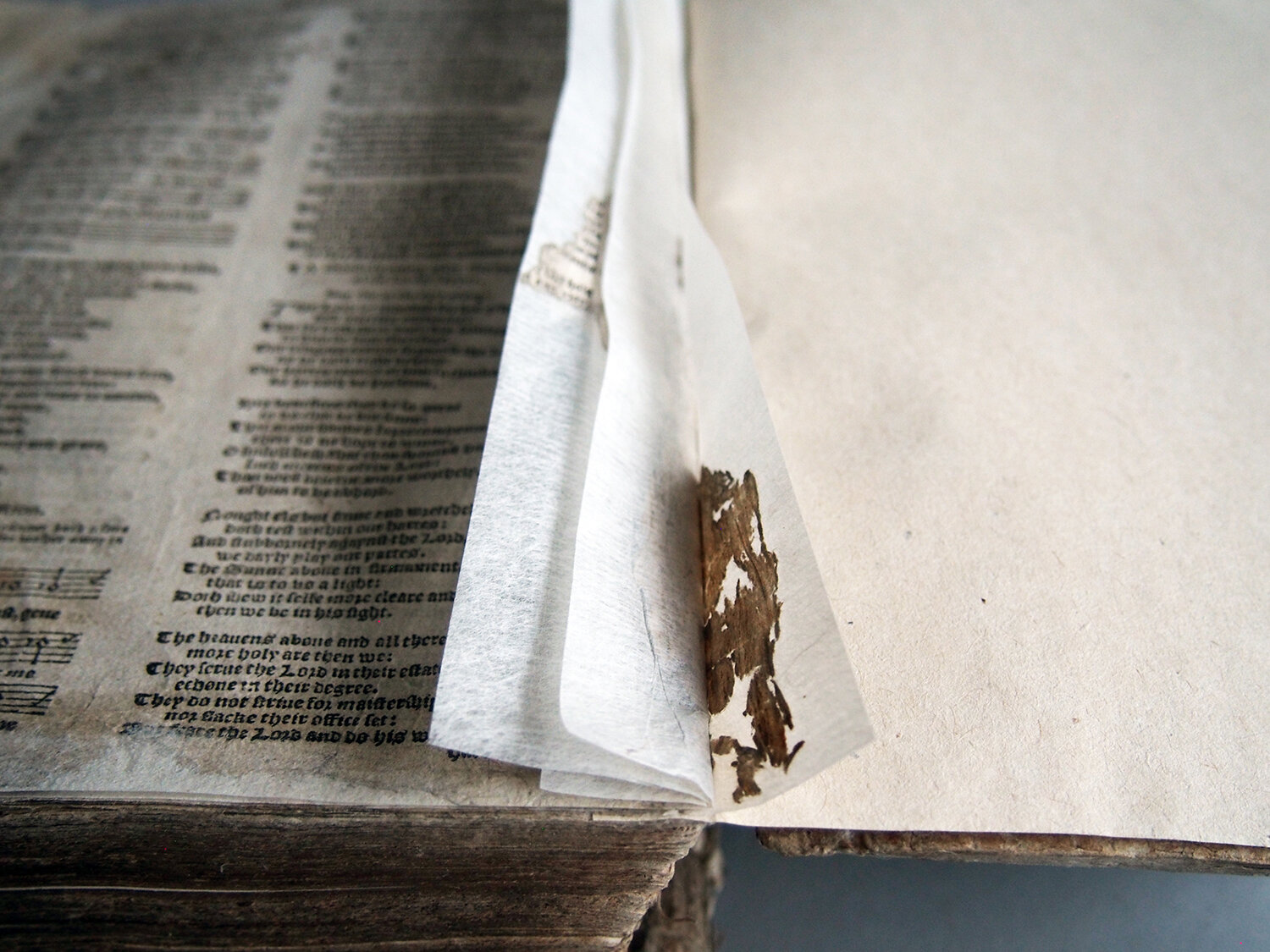

Despite quite a lot of damage to the leather and textblock, because everything was original and especially because the church valued this as a historic object rather than something that would actually be read, we decided to do a fairly time consuming but ultimately minimal treatment that involved repairing the spine folds of ripped sections, re-sewing them in situ to the supports, and supporting the spine with Japanese kozo paper to try to help maintain the little reshaping that was possible. We added supports to prevent further tearing of the leather but didn’t attempt to force the binding back into place entirely or repair the extensive damage to the boards and leather.

A Melinex jacket custom made for the book helps hold the leather in place and prevent abrasion, while being easily removable when the church wishes to display the book for events. We also made a phase box to store it in.

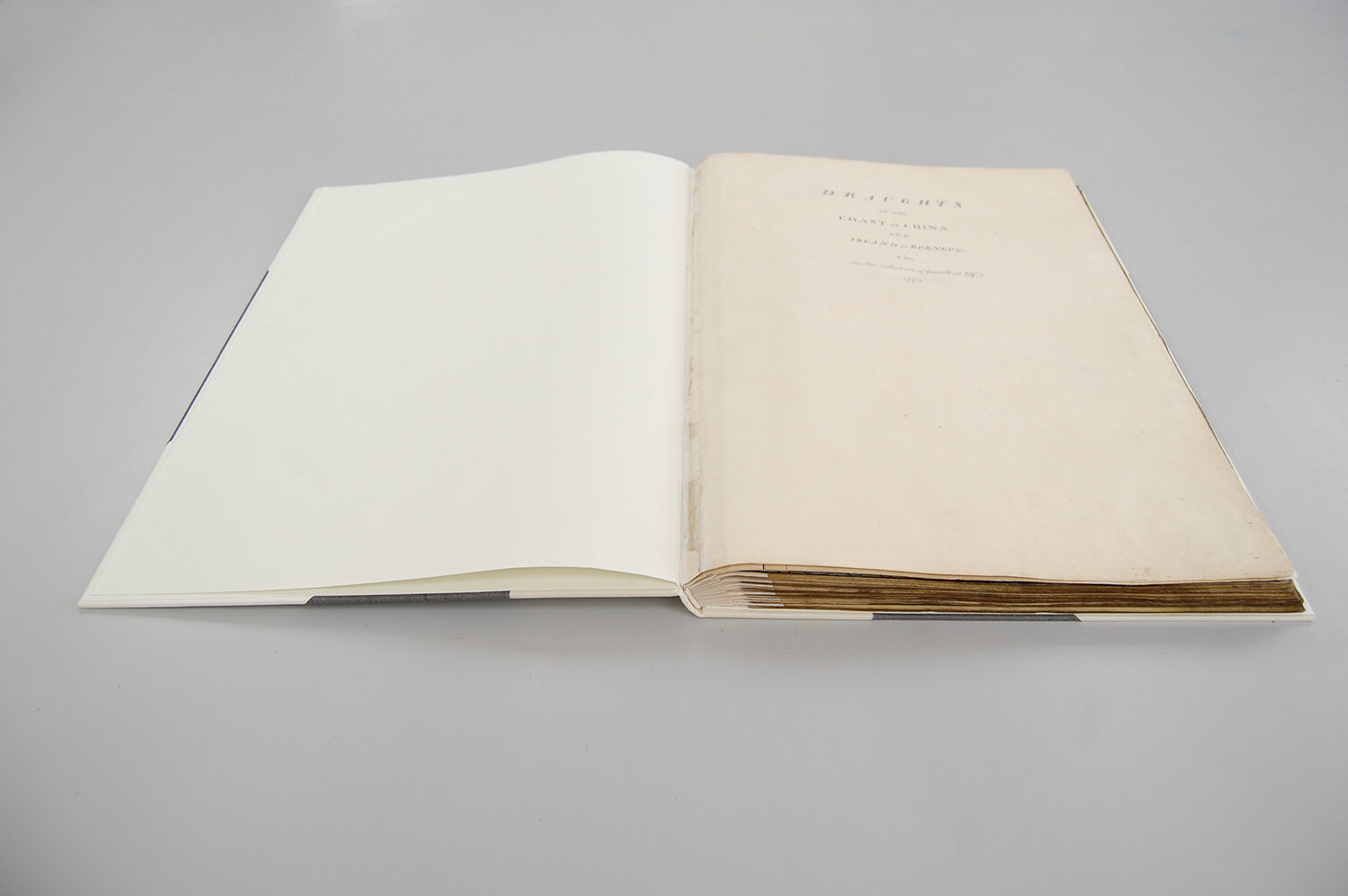

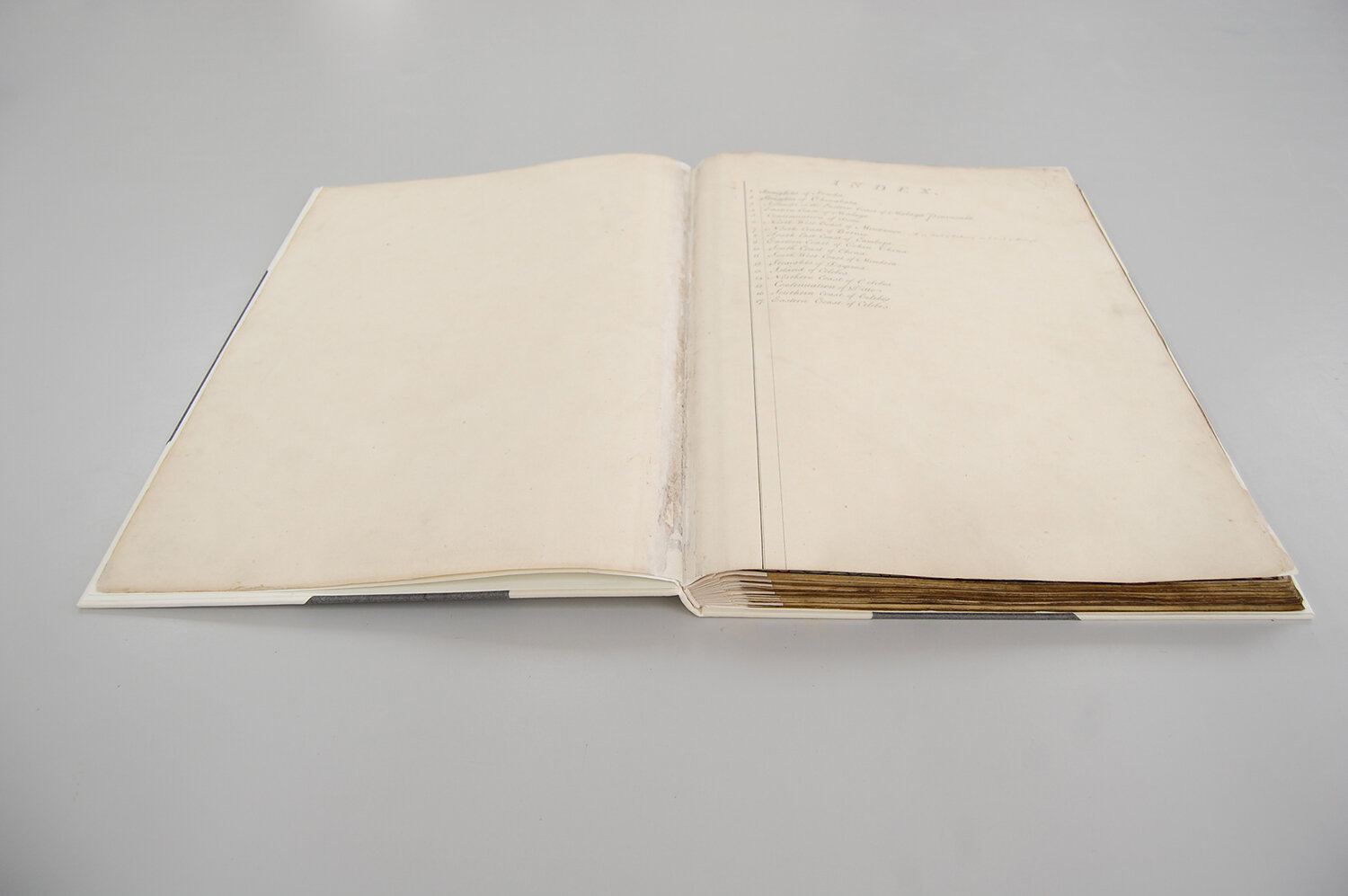

Admiralty Library

1620 Maritime Atlas

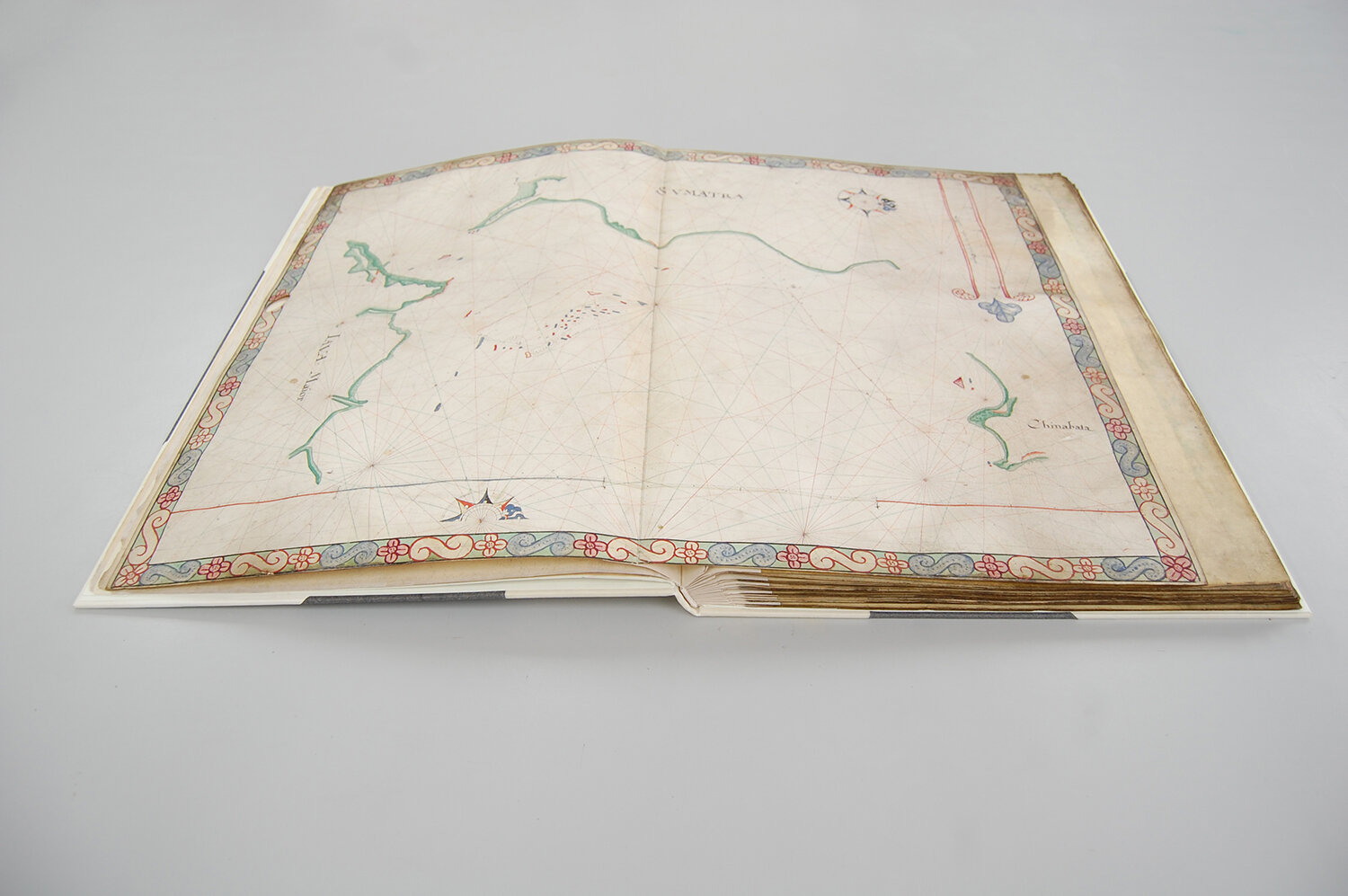

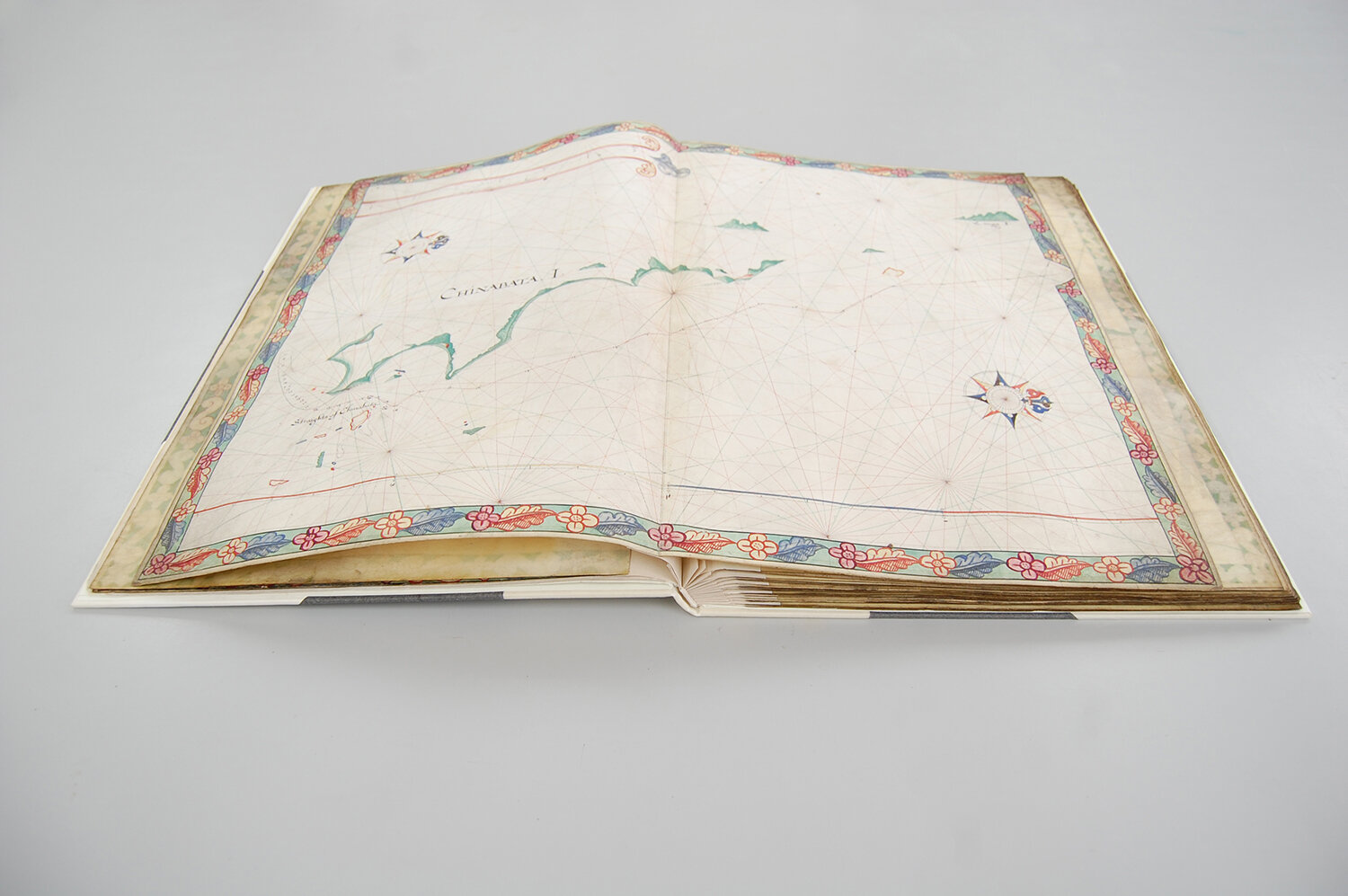

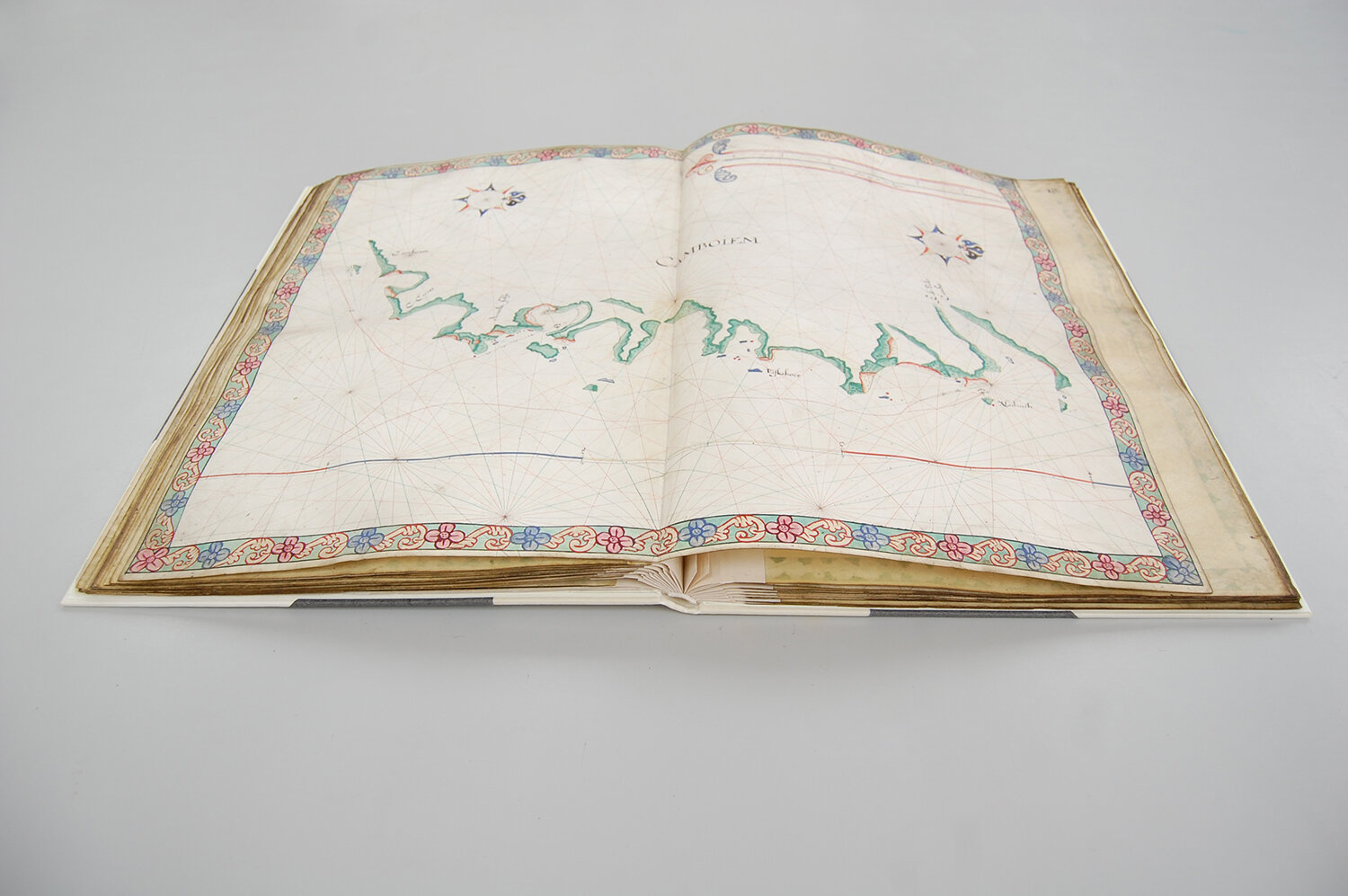

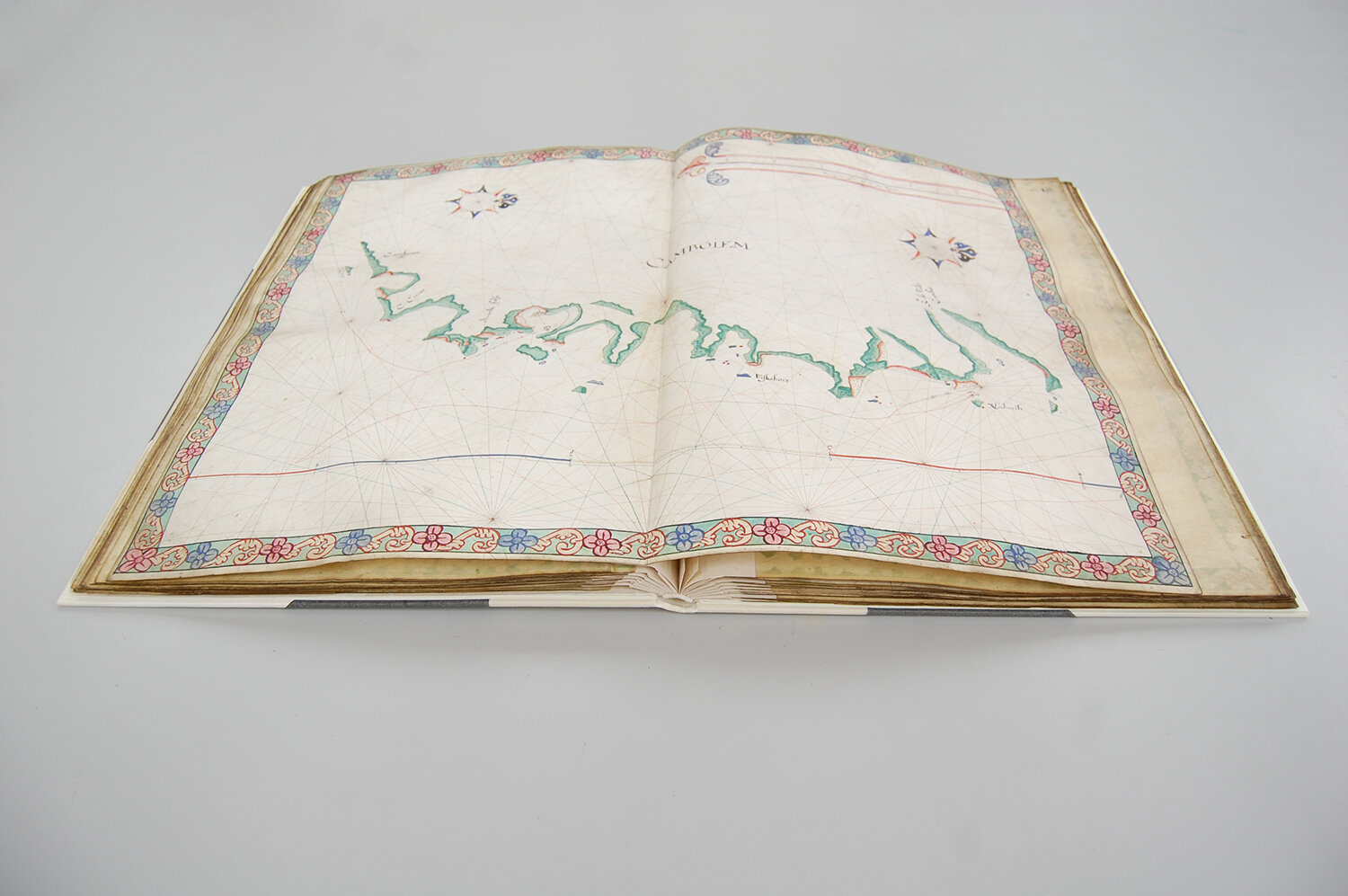

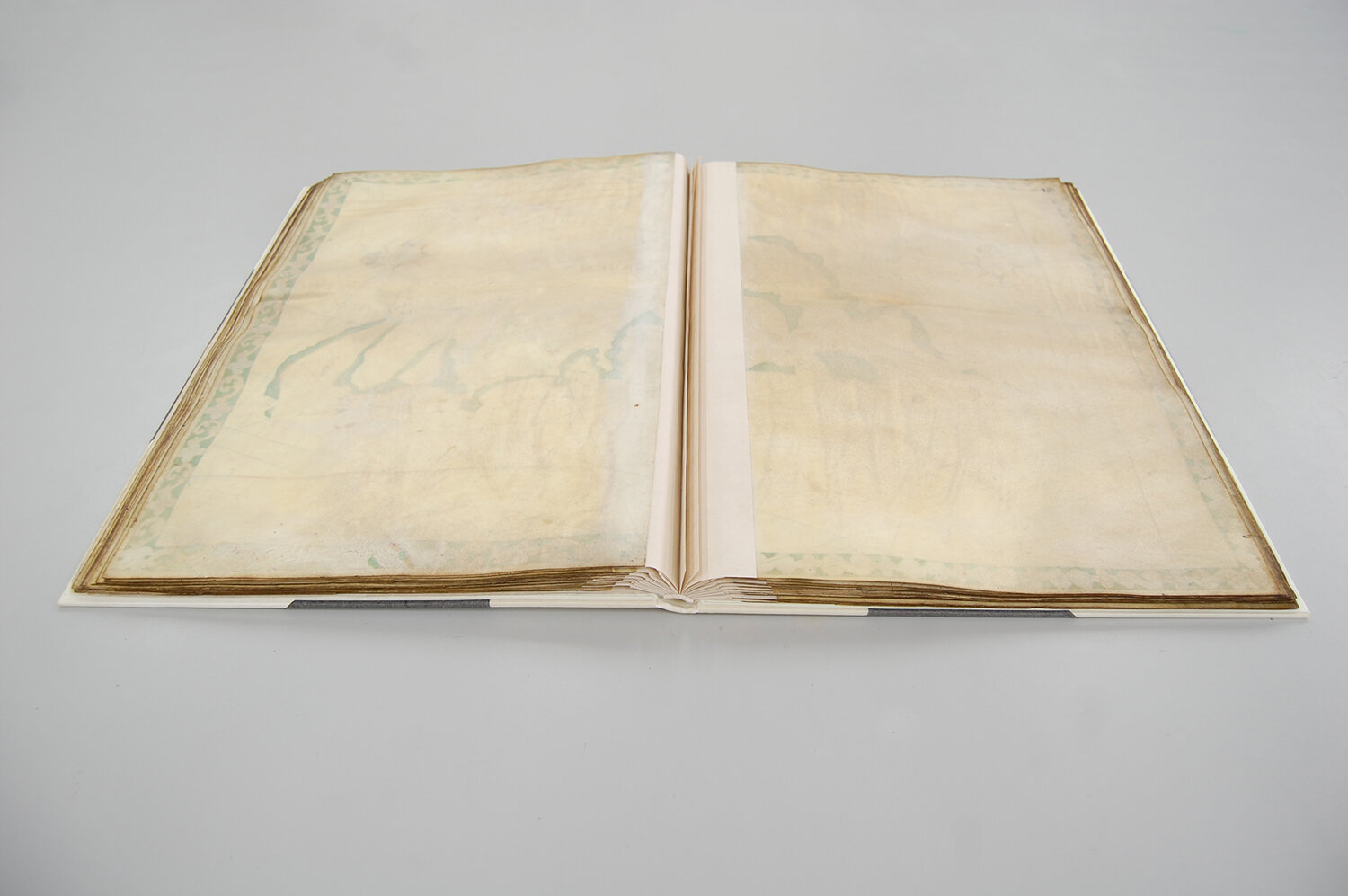

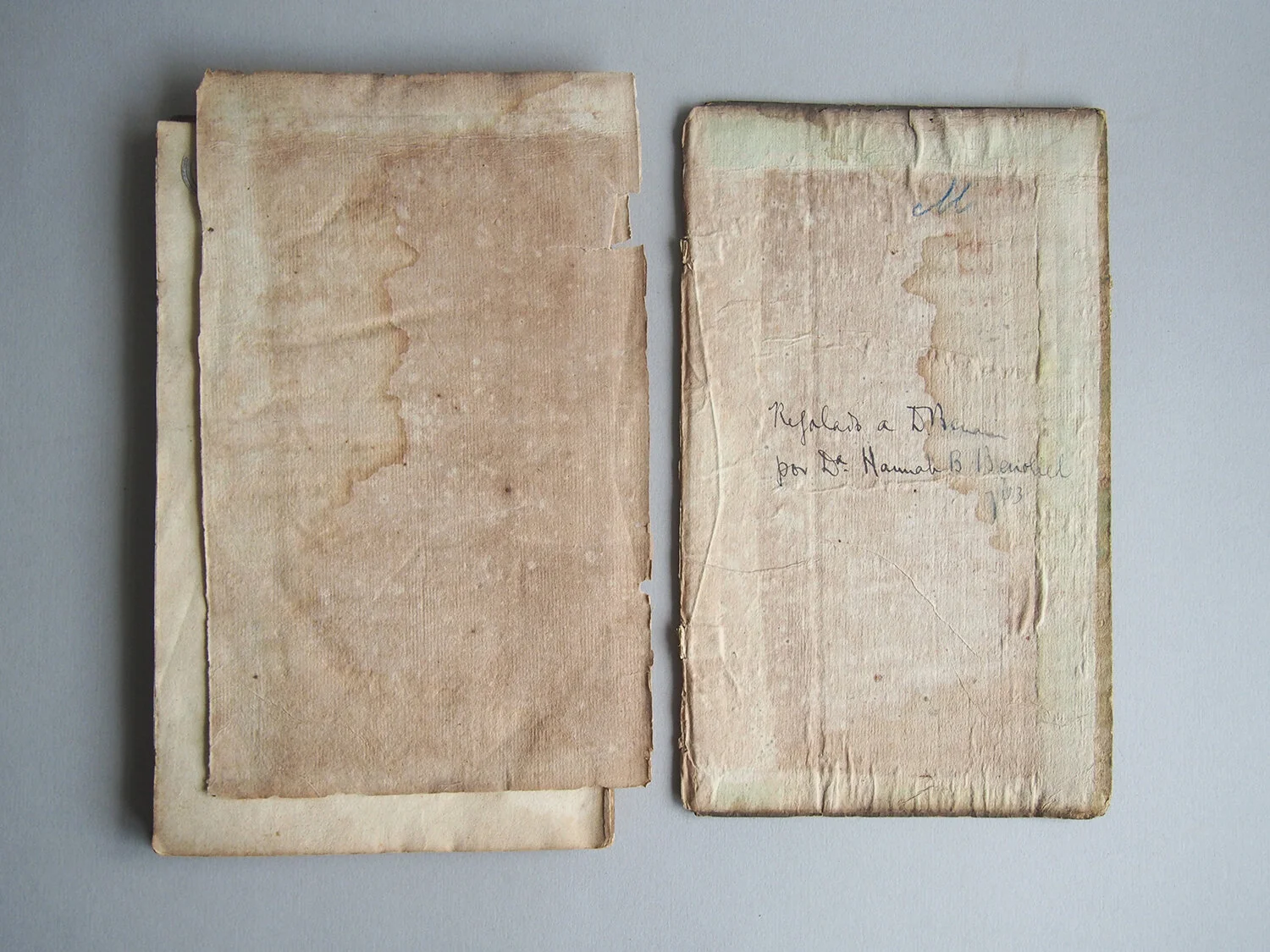

The only surviving 17th-century English charting of the East Indies, made by cartographer Gabriel Tatton. The manuscript charts were made on parchment bifolia—perhaps on board a ship!—which had originally been guarded with parchment stubs, now with paper ones. The paper was splitting where it attached to the parchment and the sewing was completely failed, so that the leaves were all separate. The paper was relatively brittle and split at the spine folds, and the half leather case binding was also failing structurally.

Before treatment detail, showing damage to the sewing and stubs.

It didn’t make sense to try to repair the guards because of the type of damage. Instead, we made new guards with handmade paper, adhered them to the parchment with BEVA film because of problems with water-based adhesives and the water-sensitive media, and re-bound the charts into a parchment and handmade paper binding that would be immediately recognisable as a new, non-original binding.

We made a drop spine box with a pressure lip to help keep the large binding closed and the leaves stable.

The new binding showing the guards, endband, and parchment spine covering.

Drop spine box custom made for the book, with a pressure lip.

private client

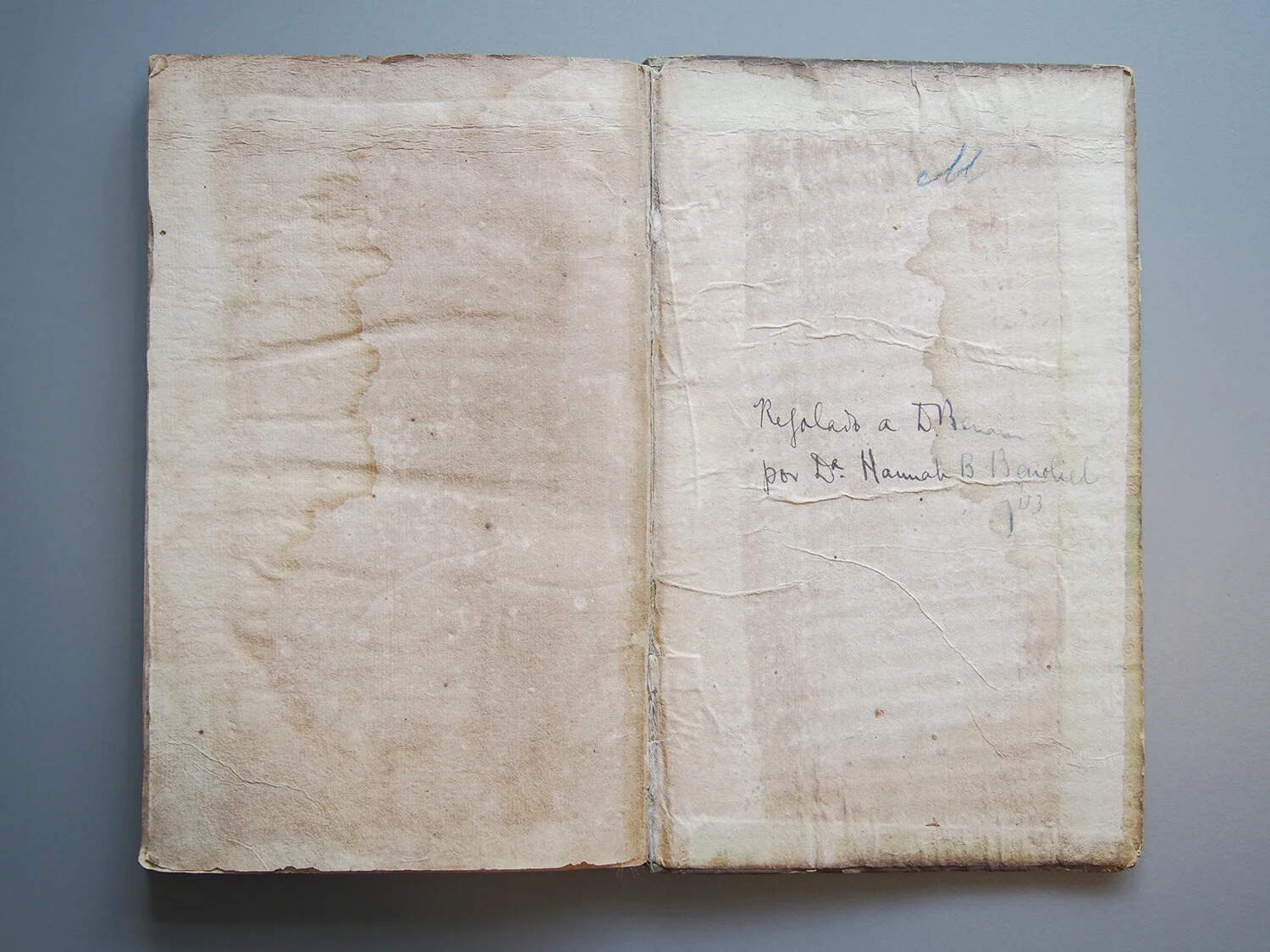

Scaleboard binding

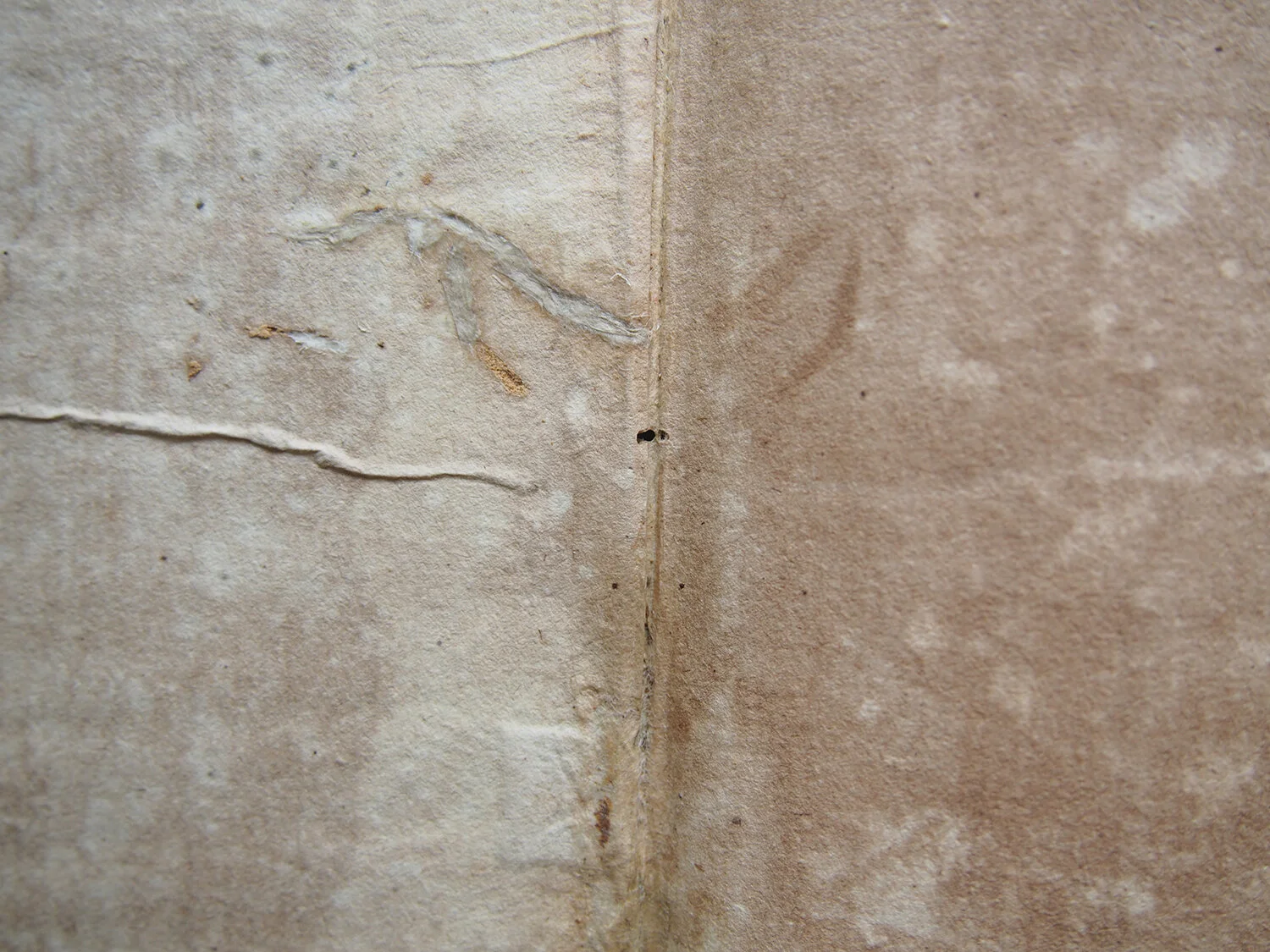

This is a scaleboard binding: the boards are made of very thin wood, covered with decorative paper. The wood has caused significant discolouration of the endpapers, and the decorative paper over the spine was damaged, threatening the stability of the binding. There was some evidence of Anobium puncatum (woodworm or bookworm) damage (see photos below on the right), leading to discolouration on the facing page where the wood became exposed.

We filled the woodworm holes in the left board, reattached the loose right flyleaf, and repaired the losses and splits in the spine covering paper with toned kozo paper.

admiralty library

McArthur Signal Book

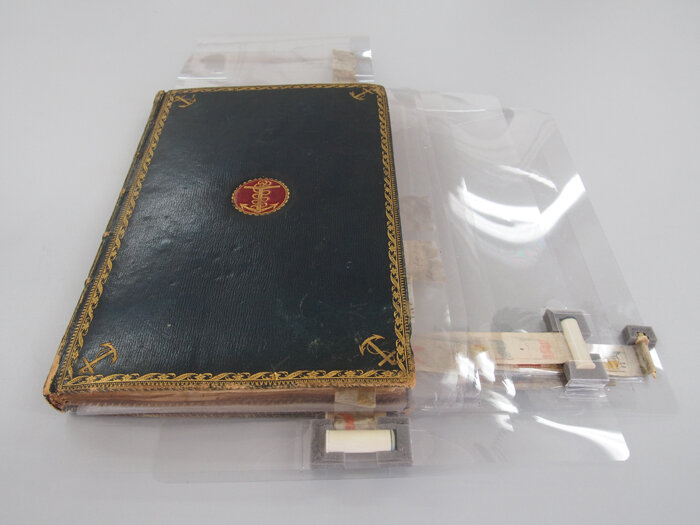

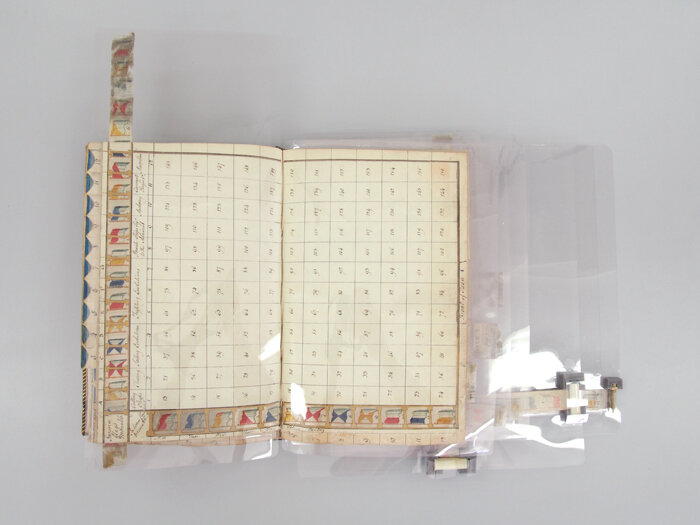

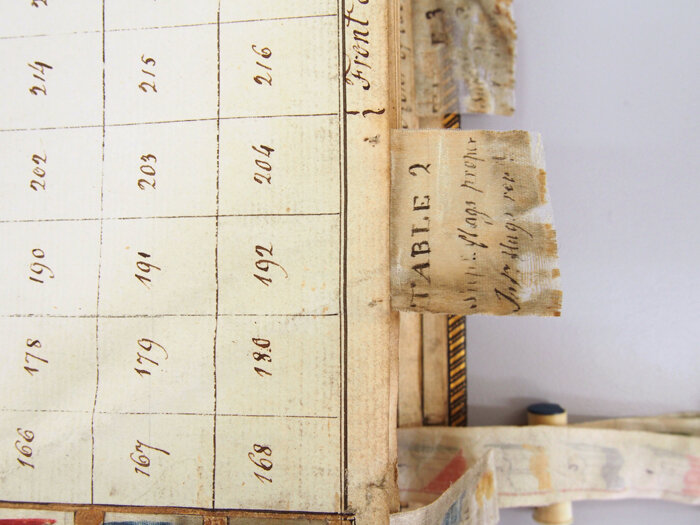

This unusual signal book (Code of Signals on a New Plan, John McArthur, 1790) bore signals painted on silk ribbons that could be pulled through the leaves to change the meaning of those signals at will. The ends of the ribbons were wound up in ivory capsules so the excess could be contained. Those made heavy ends for the delicate material, though, and the ribbons therefore suffered tears and losses, and the paper in turn was also vulnerable where they threaded through. Some of the capsules were lost or partially lost. There were also little bits of ribbon glued to the leaves as bookmarks.

The entire thing was living in a large standard archival box padded out with tissue, so there was no safe way to even remove the book from the box without putting strain on the ribbons, let alone to turn the leaves and actually use it.

We devised a system of polyester film sleeves with Plastazote blocks that temporarily encapsulate the leaves with ribbons and hold the ribbons/capsules in place. This provides support for turning the leaves, in a completely transparent way to allow consultation with support in place, but is also all completely removable for exhibition or photography.

Ribbons were flattened with light humidification and supported by heat-set silk crepoline and a few delicate paper repairs carried out where the paper was most vulnerable.

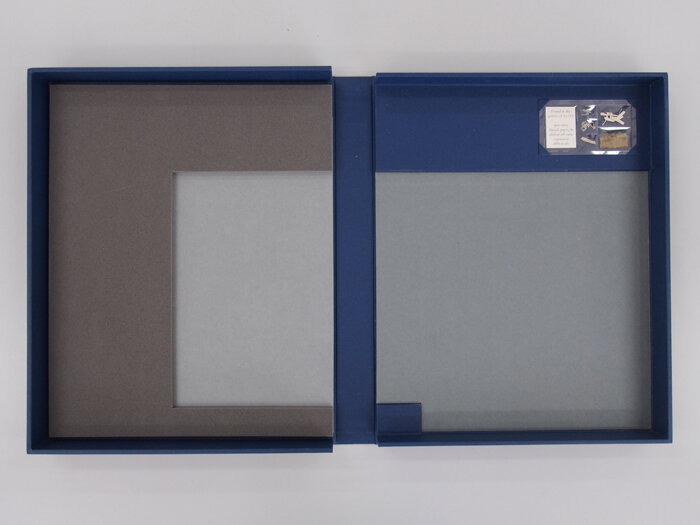

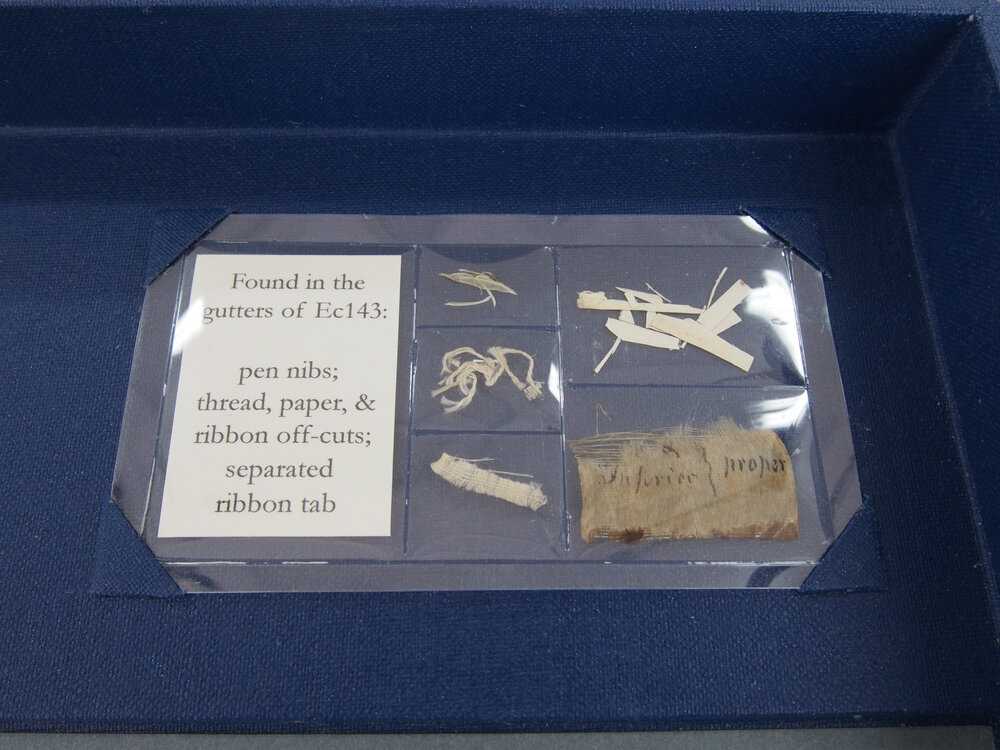

We also made a custom drop spine box to provide more secure support for the binding in storage, as well as space for the encapsulated fragments removed from the binding.